Part 1: The Acorn

Category: Travel

Photos from the Taipei Flora Expo

Taipei, inexplicably, decided to host the international Flora Expo this year. Actually, it’s a strange exhibition to put on in any country – like a small world cup, but with flowers… but holding it in Taipei guarantees that the expo will at least bring in millions of viewers if not cash to cover the expenses. I like flowers. I like trees. I love nature – but when it’s pruned and shaped and cropped, I tend to like it less. I’m still undecided about the flora expo. I went on a bad weather day, and also on an extremely crowded day. It was crowded and cloudy, the sky threatening rain the entire time. Massive lines of what seemed like every student in Taiwan (I think we went on Students and senior citizen day) made the experience far less enjoyable than a flora expo ought to be. But still. I saw some pretty flowers. Some pretty children. And some gorgeous trees that made me wish there was no one around so I could release my inner monkey and climb up. Happily the trees were there long before the expo came and will remain long after the expo closes.

|

| Kiddies at lunch. |

|

| Excellent climbing material. Excellent. |

|

| Something attractively austere about barren branches. I have many similar photos which I will one day hang in a room alongside all my furtively taken photos of bald men. |

|

| A different type of vortex. |

|

| Look at those roots. |

|

| There was a label stating what kind of flower this is. I didn’t read it. |

|

| The flora expo was close to Taipei’s SongShan Airport so airplanes came pretty close to lopping our heads off. |

Tomorrow is my last day in Taipei 😦 Hopefully for a short time.

Doing the Dougie in Shanghai (上海人 Part 3)

Like I said, Shanghai is an attitude. People just don’t care what you think. If they want to dougie, they’re going to dougie.

|

| Spotted in People’s Park. |

Or relive their old Shaolin training days…

Or roll out of bed to get milk…

This is not the same woman. Which worries me.

上海人 (下) Shanghai People Part 2

More than anything else, Shanghai is an attitude. But this post is incomplete because I often only thought to photograph people when it was too late – they had walked by, the moment passed, or it would have just been plain creepy for me to do so.

I use a small camera, not the kind that lends me much credibility as a photographer and thus am often turned down when I ask to photograph a subject. They assume, I presume, that I’m keeping their photos for a giant psycho-sexual voodoo collection. Which is true. But no, I’m joking. It lends me even less credibility when I say, “It’s for my blog.” or in China, “Boo-luo-guh.” So I have to be discreet, feeling half triumphant and half villainous, leery pervert- when I do snap a photo of someone without their knowledge… or sometimes, with them staring straight at me:

|

| Arguably the best place to read the Sunday paper. |

What I’ve noticed though, is that laborers really don’t give a damn if you take their picture. They might give you a strange look here and there, but moving to the city (most laborers are not from Shanghai but from the countryside) has made them develop a thick skin to protect them from the sorts of evil only a big city can bring out in people – what’s one young woman with a camera?

But for the most part, life is good. Hard, but good, with pockets of rest and gossip in between shifts:

|

| After each day the brooms are fed to pandas. Just kidding. But seriously, these brooms work better than the ones with bristles. |

And the shift itself, which depending on the restaurant, flies by because of the sheer volume of people you must work to feed:

|

| A different kind of sweatshop at Xiao3 Yang2 Shen1 Jian1. |

Some people make a living – and friends- fixing the darnedest things, living by an old code: “Why throw it away when you can fix it?” The economy of it amuses and inspires me:

|

| A pot mender. His shoes however, are quite new. |

There is the calm before the storm:

|

| A small hole in the wall thirty minutes before noon. |

And then the storm itself:

|

| Lunchtime. |

|

| The crowd only grew, as did our curiosity and appetite. We must have that rice! |

And if one is not Shanghainese by birth, there is the process of becoming naturalized, by force. My cousin successfully shoved her way to the front of the crowd and seized one of the last few bowls of fragrant rice.

|

| SUCCESS! |

A good day for the rice vendor; bad day for the dish washer.

All around us, Shanghai.

Looking for Old Shanghai

I’ve always liked old things. Old people, old houses, and all the old things that come with them: yellowing letters, faded photographs, dented tin cans that once held fragrant cigarettes. Perhaps it’s a psychological byproduct of being born in a young nation (Taiwan turns 100 this year) and then becoming a citizen of a nation only slightly older. Or perhaps it’s that old saying, “The grass is greener on the other side…”or in another time. Maybe it’s all the movies from the American 40’s and 50’s. Or the beautiful, rosy posters of China in the 1920’s.

Back then women did their hair, painted their lips, wore stockings and garters and painted their nails. Lights were softer back then, as were their figures and voices. Chinese Bergens and Bardots. But it’s not all glamorous. Sometimes, it really is just about the age – the forgotten time when people lived and thought a certain way.

Now, I take photos and have a penchant for overdoing the “antique” effect – I can’t help it. It brings me back to a time I will never know except from letters, books, movies…and even then, who knows if they’re accurate? But I can’t go to anywhere without trying to see it: the time on the cusp, when the city or the country was on the verge of entering the “first” world… where is that line drawn? When does a place make the leap into now? I’ll never know. Shanghai’s nearly completely there, but it’s still got at least a pinky toe in the past… I hope all cities keep at least that.

|

| The irony here is this photo was taken at Tian2 Zi3 Fang2, a relatively new establishment made to look old. |

|

| Some things never change. Chinese people believe the sun is the world’s best dryer. I agree. |

|

| Wang Ying, my cousin, took me to Qi Bao or “Seven Treasures,” a bona fide government protected old village. |

|

| Qi1 Bao3 means “Seven Treasures.” Chi1 Bao3 means “to eat until full.” The Shanghainese say, “To qi1 bao3 to chi1 bao3.” |

|

| Young people in a crowded room, making famous soup dumplings from a very old recipe. |

|

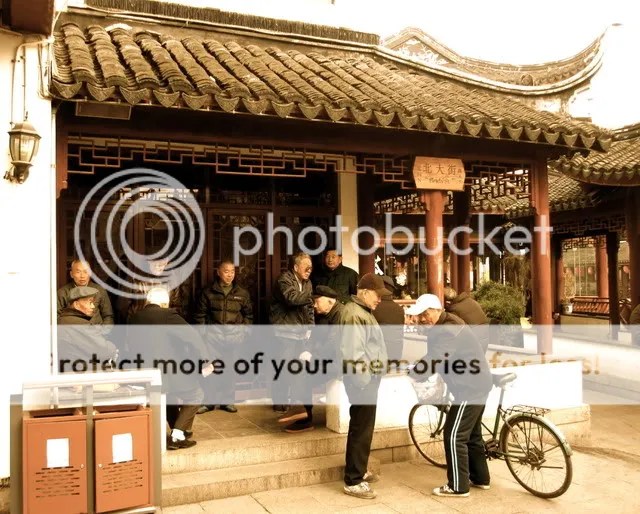

| On their lunch break, before lunch. |

|

| Upstairs at another dumpling shop, an efficient if questionable refrigeration system. |

|

| I love old furniture. But those benches are quite uncomfortable. |

|

| It’s hard to imagine how Qi Bao looked years ago with all the brightly dressed modern tourists (myself included), but I imagine the sounds and smells are the same. |

|

| Bamboo strips waiting to be woven into baskets to steam dumplings in. Sometimes the old methods are the best methods. |

Nippon, Thanks for the memories.

Tainan (Part 2) – A Village

Back from Hong Kong and Shanghai, but posting my last few Tainan photos before I forget…

After visiting the temple, Dr. Chang’s friends took us to an old village, the Chiang Family Village in Lu Tao Yang. A woman in our group was actually from the Chiang Family, and the village patriarch had been her grandfather. The village is built in the old style, courtyard units connected together, and is so well preserved that the Taiwanese government declared it a National Historical Site. There was a concert there that night, held yearly at the end of New Year’s celebrations and performed by local villagers as well as professional musicians. It was a glimpse of old Taiwan, and Mrs. Chang’s father, who went with us, enjoyed himself immensely. “It reminds me of my old home in Shandong, China,” he said.

|

| The entrance to the village had tables set up filled with games for children. |

|

| Chiang children, playing games. |

|

| One of the courtyards. Some of them are for worshiping ancestors. Such as this one. Many temples are built along the same principle. |

|

| Musicians preparing for the night’s show. The stage was set in the village square. |

|

| Volunteer ladies ladled out bowls of tang yuan, or sticky rice balls in sweet broth. You eat this for prosperity. |

|

| There was a small, moon shaped pond at the head of the village. |

|

| I saw this photo in one of the courtyards. I’m guessing it is the Chiang family matriarch. |

|

||||

| Dining hall. |

|

| An eager family, waiting for the show to start. |

|

| Costumes for the show. I wondered about the one on the right. |

As we left for Kaoshiung for our own dinner, I could hear the music start. I turned around and saw the village light up.

And for tomorrow, a preview of coming attractions…

|

| Tian Tan Buddha on Lantau Island, Hong Kong. |

Tainan (Part 1) – A Temple

Ironically, my stay in Kaoshiung offered very little of Kaoshiung. The Changs have a different way of life compared to my relatives in Taipei – the kids are shuttled around by car – partly because their parents are safety freaks and partly because up until two years ago, Kaoshiung had no metro system. The rest of the time, they study and putter about the house. They go to American school which, for some reason, means they developed American tastes and though they eat home cooked Chinese food often enough, going out, a rarity in their family, means a Western themed restaurant with a cheesy name (e.g. Smokey Joe’s, Mama Mia). Not that I’m complaining – they wine and dine me enthusiastically, thinking that because I’m American, I must like the same places – and I do, but I wonder sometimes, of Kaoshiung’s street food…

Also on the itinerary this trip was a “long” drive up to Tainan, Taiwan’s cultural capital. If Taipei is equivalent to China’s Shanghai (it’s not equivalent, really, but in concept, perhaps) then Tainan is like Beijing, where one goes to find the island’s culture. And just like the world over, people in the south are known to be extremely friendly, especially to each other… but most people I know from Tainan, aside from their ardent and often violent belief that Taiwan and China are two separate nations, live up to their reputation.

Friends of Dr. Chang offer every year, to lead a caravan to Tainan to visit a temple followed by dinner in an old village, now a government protected historical relic. The village is composed of a group of old Chinese-style homes, with four sides and a courtyard. Families start out in one unit and as children marry and branch out, they move out into their own courtyards so that a couple generations later, the entire village might be largely one family – each courtyard representing one nuclear family and connected to other courtyards by blood and brick. This particular village belonged to the Zhuang Family – and one of the women in our group happened to be the daughter of the patriarch. We couldn’t stay for dinner though, because Jenny was waiting for us back in Kaoshiung, but it was a pleasant experience nonetheless.

|

| The temple’s entrance – the stylish woman walking is actually 70 years old, the rather haughty mother of one of our group. |

|

| Guan Yin. Aka the Buddhist Madonna. She’s a bodhisattva, an almost Buddha, basically. She’s supposed to hear your cries and wails and offer aid. |

|

| Nun on a cell phone. This really bothers me, for some reason. Just as it bothers me when I see Buddhist nuns and monks at Disneyland or at Narita Airport in Tokyo, shopping for electronics. |

|

| Don’t know who this is, but gold plated stuff photographs beautifully. |

|

| A giant rock standing before the actual worship house. The giant character in black means “Buddha.” |

|

| Following a boy in yellow down the pretty path to the actual temple. The nun first took us around some warehouse of expensive relics. |

|

| The brightly dressed boy feeding even brighter fish. |

Tainan Part 2 coming next week, followed by Hong Kong (if I get any photos) and Shanghai. I leave at 4 am tomorrow morning for a flight to Hong Kong to get my Chinese Visa. I’ll arrive in Shanghai at 10pm and stay until Monday morning. It’s a bit early, but a happy weekend to you all 🙂

Real Convenience

Ask people in Taiwan who have lived abroad but decided that Taipei was still the city for them their reasons for returning, they will invariably reply, “Taipei’s convenience – you just can’t beat it.” Kaoshiung is getting there, with the relatively new metro and slowly but surely expanding city center, and with the High Speed Rail linking the southern capital with the northern capital with a 1.5 hour train ride, an American wonders what’s taking the Los Angeles to Las Vegas High Speed Rail so long to become a reality.

So this is why convenience is for me, redefined every year for me in Taiwan. I book the High Speed Rail tickets online. And then I go, “Oh crap, I have to go and pick them up at the train station? What if I get lost? What if I’m running late?” The website tells me, “You don’t even have to pay online. Find your local 7 Eleven, then pay and print your tickets there.” I say, “Wow,” and leave to get my tickets.

A few days later, I walk to the metro station which takes me to Taipei Main Train Station, where I take the stairs a few flights directly above the metro line and breeze through another set of turnstiles. The train is there, a silent, giant beige bullet (with an orange and black stripe -tiger colors – for the illusion of even more speed), waiting to whisk me and a few hundred more people to major cities down the length of Taiwan (and inexplicably, one city rather close to Taipei).

|

| Like lightning! |

|

|

| The train’s bright and clean interior. |

Despite its convenience, the HSR is still very expensive compared to the buses: it costs 1,450NT or roughly 50USD for a one-way trip all the way south while the most expensive buses are still less than 400NT (12USD). But it’s a 1.5 hr. trip vs. a four or five hour bus ride. I’m lucky I don’t have to take the bus.

|

| The train floor was a confetti party and my shoes, Superga Party Editions. |

I spent an minute or so staring at the floor and then at the young man with a crazy haircut on my right. He was texting with his girlfriend and was mesmerized by her excessive usage of emoticons. And right when I decided, “Enough! I ought to read!” and reached for my book, the train slowed to a stop. Voila. High speed. I was there.

The Changs in Kaoshiung

Every trip to Taiwan also means a visit down south to Kaoshiung, a port city at Taiwan’s southernmost tip. Distant relatives live there, and by ‘distant’ I mean my grandfather’s uncle and his children, a warm and energetic young couple whose kids are supposedly my aunt and uncle…or something like that. But they are by no means ‘distant’ in the emotional sense of the word. I watched their children Wayne and Jenny grow up just as they watched me grow up and now, with Jenny on the cusp of graduating from high school, I am beginning to feel the wistfulness that comes with seeing someone younger and more hopeful.

Distantly related though we are, it makes me happy when people look at us and assume we are sisters. According to her parents, Jenny admires me, learns much from me, but when I look at her, I see a young girl more self-assured and generous in heart than I was at that age. Now nearing twenty-five, I feel there is much I can learn from her. Her eyes are bright, her smile wide, and her hopes great but not so that she should be unwittingly crushed beneath their weight. I seldom hear her complain about her impossible workload (it is whatever I underwent during high school multiplied by one hundred) and when she hits a road block, she says, “I can figure it out. I can find a way.” If these are qualities she learned from me, let me rifle through my memory and revisit that young girl.

|

| Jenny and I. See the resemblance? |

Jenny attends Kaoshiung American School, an impoverished but acceptable counterpart to Taipei’s more financially robust version, and is contemplating spending her senior year abroad at Philips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire (where Mark Zuckerberg went). Wayne graduated from KAS two years ago and is now studying electrical engineering at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh, whose cold and demographics are a far cry from the balmy tip of Southern Taipei, where diversity equals a handful of Chinese Mainlanders.

They are a simple family, in some ways very similar to the Taiwanese folks they’re surrounded by, and in some ways very different. Nearly six years ago I visited the United Kingdom with them and all together, we fell in love with the rolling green hills of Edinburgh and the bustling metropolitan of London. Wayne was about to start high school then and Jenny was a sixth grader – both, under their parents support and encouragement, were strong students with many talents and lofty academic dreams. I was a college dropout still trying to figure things out.

On a ferry ride to a place I remember by sight but have forgotten by name, I stood at the railing with Mr. Chang (for simplicity’s sake, I’ll call him Mr. Chang, when really he’s something like a great uncle or cousin), watching houses and ducks glide past as he told me, in his own way, that it doesn’t help to plan what we can’t know. “I was just beginning medical school when my father sold his watch-making business and bought a hospital,” he said, “The expectation was that I would graduate and head the hospital. It was a huge responsibility that came with enormous pressure. More than I could bear. When I graduated, I told my father no, I couldn’t accept the hospital. I wanted to start a small clinic and lead a simple life.” He did just that. He owns and operates a small, brightly lit clinic just steps away from where they live and because he sees his clients with a surgical mask, his patients stare at him blankly on the street when he waves to them and only come alive when he speaks. It is still hard work – he works from eight am to nine pm each day, and only takes vacations every other year or so when he can find a trustworthy and willing physician to take his place – but it is what he loves.

Mrs. Chang is a psychologist, a relatively new science in Taiwan. She specializes in sand therapy, which in the realms of psychology, is also relatively new. Her clinic occupies the floor above her husband’s and in the brightly lit space, one will find shallow boxes filled with sand and cabinets that open to reveal hundreds upon hundreds of miniatures: dolls, furniture, plastic shrubbery, cars, etc. Anything that you can think of, she has, only in miniature. The therapy consists of patients starting with an untouched box of sand and being encouraged to shape the sand anyway they want and to place upon it carefully selected miniatures that reflect, supposedly, their state of mind. Meanwhile, my aunt stands quietly by, scribbling notes and nodding and, when the patient is through, taking a photograph of your “work.” The sandscape changes when you are making progress, or regressing even, and only when you’ve plateaued emotionally does the sandscape remain static. (This last bit is my conjecturing). In 2005 I visited her clinic for the first time and made my own sandscape. A year later, I made another. I remember placing tiny plastic palm trees alongside sitting room furniture – whether this scene occurred in the first or second sandscape, I’ve forgotten. The photographs are stored somewhere on Mrs. Chang’s hard drive alongside her abundant notes and, I hope, her diagnosis that I have achieved emotional stability. Though she struggled to find clients in the beginning, is now steadily seeing five or six patients per week as Taiwan begins to accept the fact that yes, their society, like all societies around the world, is filled with crazies.

|

| Mr. and Mrs. Chang. |

Their home in Kaoshiung bears her touch most distinctively. Like me, Mrs. Chang is neat. Not a freak about it, at least not by my standards, though her friends chide her and say she is “compulsive.”

|

| Their family study center. Neat. |

But fascinating to me, her person always seems slightly disheveled. Her clothes, though neat in the wardrobe, seem to wrinkle on her slight frame and her hair, despite the warm coaxing of an ionic Japanese hair dryer, remains wispy and unruly. She is the soft-spoken, clumsy wife of a rather severe looking doctor, but her brain is sharp, as are her eyes, from years of study and discipline. She adores Laura Ashley, lavender and Josh Groban and though her mother died two years ago, taking to the grave her secrets of Chinese northern-style cuisine, Mrs. Chang has recently discovered the joys of cooking. She lovingly prepares healthy meals for her husband, children and her father, now widowed, now eighty-nine.

Mr. Shen is my mother’s father’s uncle. Does that make sense? But they are roughly the same age. He too, is from Shandong Province in China and despite many years away from the mainland, he retains his hearty Shandong accent. Though his wife passed away two years ago, Mr. Shen adheres rigidly to his daily routine. To assert his independence, he lives in a converted studio above Mr. Chang’s clinic, though he dines and spends most of the day at his daughter’s home. Every morning, he is up at five, eats a simple breakfast of toast and milk (powder from a can because he likes it hot) and takes a thirty minute stroll around the park. Then he walks to the house, lets himself in and settles down in the living room where he reads the paper. Then he sits quietly as the family moves about him, getting ready for their own days. Mr. and Mrs. Chang leave for the clinic, Jenny for school, and then it is just him and Teswi, the Indonesian maid whose Chinese is poor and whom Mr. Shen addresses with a wave. “I don’t know her name,” he said to me, “I wave at her, and if she happens to see me, she’ll come.” In the afternoons after lunch, which is usually heated leftovers, he returns to the park to sit and chat with other retirees and grandmothers, many of them from Shandong like himself. Now a bachelor, he finds himself quite popular amongst the park’s older women, many of whom now widowed, see him as something of a catch. One of the women told Dr. Chang during a check up that she thought his father in law was “the most gentlemanly out of all the fellows” who frequented the park.

“They know I’m Dr. Chang’s father in law,” he told Mrs. Chang one evening, about a year after his wife passed, “They know that if they take up a companionship with someone like me, they’ll be in good hands.”

“Then why don’t you…” His daughter searched for the right word, “…date some of these women? It’s never too late to love another.”

“Ha!” Mr. shen said, “At my age, it’s more costly to enter into one serious relationship than it is to entertain a hundred acquaintances at the park. I’ll keep things as they are, thank you very much.”

When he’s finished with the paper, he sits quietly in the living room, staring at the opposite wall with his arms crossed. Two or three times a week the phone will ring during these quiet mornings and it will be his son on the other line, calling from Irvine, California with news of his grandson, Dennis, who is currently waiting to hear back from colleges. Mr. Shen eagerly waits to hear of Dennis.

I arrived in Kaoshiung on the night of his eighty-ninth birthday, for which his daughter made him braised pork knuckles and long-life noodles. He was already in bed, so I saw him late next morning. He was sitting, the paper already folded before him. I brought my toast to the living room to say hello. He greeted me warmly, just as my own grandfather would, and then the phone rang. It was Dennis’ father. I heard bits and pieces. “Illinois?…Is he going to go?… Ranked third, you say? Well that’s quite excellent, isn’t it? Third! In America!”

Later, as he sat eating his lunch – the last braised pork knuckle and knob of noodles – he asked me how much a small car costs in the United States. He was thinking about buying Dennis a car for his graduation. “He’s a good boy, you know, got himself into the third best electrical engineering department in the United States. Such a good boy. Many talents. Plays the saxophone and football and won the world championship for an art contest. Ranked third, that school in Illinois. No doubt he’ll need a car…”

|

| Long life noodles. But not if you finish the whole plate… |

I looked at the park’s most eligible bachelor, his lips gleaming with pork grease, his face glowing with pride. I tell him that a suitable car for a kid like Dennis should cost about 15K. Twenty, if he’s feeling generous. “You could even get him a nicer car, used,” I say, but he shakes his head. Probably not used, he says, Dennis is such a good kid. Did he tell me that school in Illinois is ranked third? Third! In the U.S! Believing that to live long one should only eat until seventy percent full, he proceeds to cleans the pork knuckle but leaves a bit of noodles on the plate.