Tag: Taiwan

100 Years of Vanity, Part III

100 Years of Vanity, Part 1

July

My grandfather was interred on a hillside in the outskirts of Taipei city on a muggy July afternoon. As tradition dictated, we turned our backs on his coffin as the gravediggers dropped him into the ground. There is nothing sinister about a man dying from old age, but there is too much mystery about death to take chances, so by turning away, we were protecting our spirits from following his into the grave. Continue reading “July”

Photos from the Taipei Flora Expo

Taipei, inexplicably, decided to host the international Flora Expo this year. Actually, it’s a strange exhibition to put on in any country – like a small world cup, but with flowers… but holding it in Taipei guarantees that the expo will at least bring in millions of viewers if not cash to cover the expenses. I like flowers. I like trees. I love nature – but when it’s pruned and shaped and cropped, I tend to like it less. I’m still undecided about the flora expo. I went on a bad weather day, and also on an extremely crowded day. It was crowded and cloudy, the sky threatening rain the entire time. Massive lines of what seemed like every student in Taiwan (I think we went on Students and senior citizen day) made the experience far less enjoyable than a flora expo ought to be. But still. I saw some pretty flowers. Some pretty children. And some gorgeous trees that made me wish there was no one around so I could release my inner monkey and climb up. Happily the trees were there long before the expo came and will remain long after the expo closes.

|

| Kiddies at lunch. |

|

| Excellent climbing material. Excellent. |

|

| Something attractively austere about barren branches. I have many similar photos which I will one day hang in a room alongside all my furtively taken photos of bald men. |

|

| A different type of vortex. |

|

| Look at those roots. |

|

| There was a label stating what kind of flower this is. I didn’t read it. |

|

| The flora expo was close to Taipei’s SongShan Airport so airplanes came pretty close to lopping our heads off. |

Tomorrow is my last day in Taipei 😦 Hopefully for a short time.

Spring Cleaning

A few days ago was Qing Ming Festival, when Chinese families visit their ancestor’s grave and give them a good scrub.

|

| A Taiwanese cemetery. |

A few years ago, this was actually necessary. Families would load up their cars with brooms, dustpans, pruning shears, etc. to tackle the natural growth that would eventually creep up over the tombs, which are much larger than standard American grave plots.

|

| Where Grandma and Grandpa Ho are buried. |

When the weeds had been pulled out, the bushes and grasses trimmed back, and fresh flowers, fruit, wine, and whatever other edible offerings set before, burning incense would be placed in a small pot before the tomb. Incense signifies a spiritual vigil. The living light incense for the dead, or for the Gods, to show that we still respect them. Incense also marks a sort of connection between the two worlds; once the incense is lit, we are in conversation with the dead and it is while the incense burns that we believe our ancestors are consuming our offerings. After the ancestors have eaten and drunk their fill, we burn paper money for them to use in the afterlife. At the markets, one must be sure to buy the right currency: Ghost or God money cannot be burned for Ancestors and vice versa.

Nowadays, at least in Taipei, grave cleaning is unnecessary. We were lucky to find a quiet cemetery with spacious plots and tiled floors. Once a month, we pay a maintenance fee, like you would in a high-end apartment complex and the caretakers come and do the cleaning for us. Some people forget to pay the fee, and their ancestors’ graves are noticeably neglected.

|

| Whoever lies here is writhing in shame. |

But in Taipei county, land is scarce and plot burials are now rare – reserved for those who had the foresight to buy a plot early on. If you didn’t make such an investment, its cremation for you. My grandfather was the last person in our family to have a traditional, whole-body burial – the plot was bought many years before, when his third wife (and my biological grandmother) passed away. When he lived, we came once a year to worship our grandmother and our father’s great grandmother, who is buried in the neighboring plot, but my grandfather never came along. And why would he? In the second photo, the characters on the tombstone are painted gold, but they’re only gold when the person has been buried. For many years, my grandfather’s name was still in red, signifying his status as a living man.

Also for many years, Grandpa would wait patiently for us to finish eating lunch so he could go home and take an afternoon nap. Now, we wait for him.

|

| The adults talk about where to go for lunch. My uncle (seated) was eating vegetarian that day. |

|

| My uncle takes a work-related call. |

|

| My cousins complain about work. Melody (left) works at a bank. Karen works at PWC. |

|

| Almost there…not. |

|

| To kill more time, Karen resorts to playing Angry Birds (and then checking Facebook) on our great great Aunt’s grave. |

Finally, our grandparents and the Gods alike have feasted and it is time to burn paper money.

|

| May they shop in peace. |

Last year’s grave cleaning marker is removed – a stack of red paper left on the tombs to signify that the relatives have come and paid their respects:

And replaced by a new marker.

|

| Cleaned. |

Until next year, Grandpa.

Little Cat

My aunt has two cats – a fat yellow cat and a less fat dark, striped one. They’re called, fittingly, Big Cat and Small Cat. My aunt never saw the need to give them other names. Big Cat’s problem is he mews whenever he wants to eat something. Which is always. He also doesn’t move. Like some people I know. Small Cat is more active. He’s also more jumpy – the first to disappear if a stranger comes into the house. Small Cat’s problem is he likes to pee on things: clothes, blankets, pillows, and once, my aunt’s head. He also has this weird thing where he likes to fit himself on a tiny platform. Because he pees a lot, no one puts him on a pedestal. So he does it himself.

|

| Cat on a pseudo-Victorian novel. |

|

| Cat on a small woven box. |

|

| Cat dozing on my uncle’s laptop. |

|

| Cat stirring on my laptop. |

|

| Cat on a cookie box. |

|

| Cancer cat. (Shortly after this photo was taken my aunt shooed him away). |

|

| Cat in a box of junk. |

|

| Cat on a boxed vase/urn. I think. |

|

| Cat on a stack of finance magazines. Money cat! |

|

| Cat on my aunt. Happy cat 🙂 |

What an outrageously pointless post.

Grandfather’s Office

Every morning up until the month before he passed away, my grandfather went to the office with his two sons. For thirty years or so his official title was company president, his presence necessary at all company meetings and his opinion of utmost importance when it came to decision making, but sometime around his ninetieth birthday he decided to take a step back and let his sons take the reigns. He was still the man who signed the checks, an activity he delighted in, but he shortened his working day to four hours, eight to noon, when he would leave for lunch. As the years wore on, his “duties” became a lightweight medley of newspaper reading and reorganizing the whirligigs on his desk and matching lottery numbers. From time to time he would emerge from his office to see what his sons were up to, and they would look up from whatever they were working on to nod kindly at him.

Often, he would tap on his middle son’s window and ask how the stock market was doing.

“It’s doing fine, Father,” his middle son would say, “Just fine.” And my grandfather would nod and shuffle along, a stooped figure gliding past the glass.

It is good fortune, the Chinese say, to be emotionally close to one’s family and even greater fortune to be physically close. Ask any elderly Chinese what it is they want most and most likely, they will say, “To have my children all around me.” My grandfather was blessed by living in the same building as two of his sons and their families, and doubly so in that he worked with them as well, without incident. My grandfather’s sons were the light of his life, the company they had built together a great source of pride. That his sons respected him is an understatement – they showered him with love and adoration, but of the quiet type. There was never any fawning, only a steady stream of support and acquiescence for whatever it is the father wanted to do.

It seems silly to point this out, but they let grandfather have the biggest room. That expansive back office with long windows overlooking the neighboring airport.

Once, when I went with grandma to pick grandpa up for lunch, I found him dressed and ready to leave, standing before the window, watching the planes take off.

“He likes to do that,” my uncle told me.

When my grandfather passed away, there was no question as to whether the room would be cleaned out for either uncle – it wouldn’t. His sons would leave it just as it was. Visited the office last week, I found it unchanged since the last time I went to pick grandfather up for lunch. The room was slightly colder, but clean and orderly, with the desk chair pushed back and a pen left uncapped on the desk, as though grandfather had left briefly and would be returning any moment.

I examined his things, though I had seen them all before. It was like rereading a favorite book.

My grandfather was a shameless collector of cheap toys.

And clocks, of any type.

His shelves were decorated with gifts from friends, including this stone rooster, complete with pebble grains. My grandfather was born in the year of the Rooster, as was my brother, my grandmother, and two aunts.

Behind a small table set from the seventies, a collection of Chinese paintings, also gifts from friends and business partners.

There were also many mirrors to be found, as even more than airplanes my grandfather loved to look at himself.

In the small wardrobe, a large safe, a crisp white shirt and a portrait of his father. Once, while helping my grandfather with his coat, he saw me looking at the photograph. He smiled and slowly lifted his hand up to point at the picture; he was nearing one hundred years old then. “My father,” he said, “my father.” Fittingly, in each of my uncle’s offices, there are portraits of their father.

And on the adjacent shelves, more recent photographs:

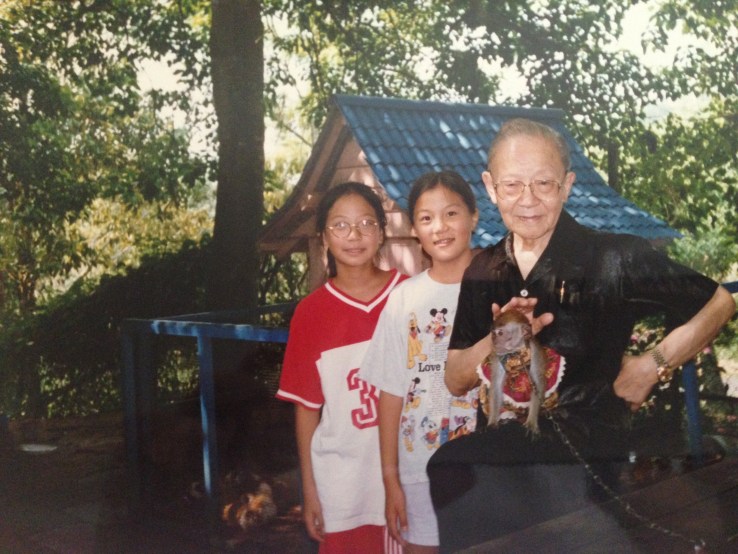

|

| From a company/family outing with the office ladies and grandchildren. |

|

| With Grandma on the left (peeling shrimp for Grandpa), Betty and Grandpa at one of many restaurants, circa 2007. |

In the Company of Single Women

Forty-six years ago, my grandfather retired from his position as a customs officer and with fortune’s second wind, established a small company, the workings of which to this day, remain somewhat of a mystery to me. I once asked my second uncle what it was the company did. Looking up briefly from his computer screen which, as usual, was covered with blinking red and green numbers, he shrugged and said, “I know what I do for the company, but other people, I’m not quite sure. A smattering of things, I guess.”

|

| First Uncle Kwang-Hong, the middle brother, in his office. |

At its inception it was a medical supply trading company and only later, with my grandmother’s death, began its foray into real estate development. She had wisely bought random parcels of land throughout Taipei, leaving it to her sons who in turned built office buildings and tall condominiums upon it when they were grown and joined the company’s ranks.

|

| Project drawings from the company’s heyday. |

Why, people ask the children in our family, don’t we just “take over” the family business? It was and remains modestly successful and, were we to infuse it with youthful innovations, surely it could rise to become even greater?

|

| Where important meetings once took place, old files and boxes of supplies pile up. |

Fat chance, we reply, not least because the office exudes a musty smell and a blanketed quiet – all signs of a company in decline. The boys are off hunting bigger fish (i.e. companies that occupy more than just a single floor) and the girls, well, we can’t help but think of all the office ladies who in the company’s heyday, were still pretty young blossoms waiting to be plucked from white collar obscurity. Now however, they are old maids. Family lore has it thus: if you are a single woman entering the company’ work force then you will leave a single woman. It’s the company curse, and a notably sexist one at that. Men who work at the company will eventually find themselves happily married to wonderful wives who bear even more wonderful children (case in point: me). This is precisely what happened to my grandpa, uncles and father and a smattering of other men who have come and gone. Women however, risk an eternity of spinsterhood.

|

| Doomed. |

Of the six women who have begun their careers with us, only one is married, and this occurred prior to her employment. The other five have given up looking for love, it seems, though I can’t say for sure. I doubt women ever stop looking. They dress up to come to work, though there are no men to impress but my two married uncles, one of whom is almost hermit-like. The company’s one man financial analyst, he closes the office door each morning, hiding behind four giant computer screens until lunchtime, when he steams his home-packed lunch, inhales it, then settles in for a nap. He rarely speaks to anyone, bidding only good morning and good night to the office ladies.

|

| An artist at work. |

My other uncle, my father’s youngest brother, is a bit of a workaholic. When he is kind he is very kind, but when he is angry, the entire office cowers beneath his oppressive anger. The women fear him, but they also cannot leave him. It is a strange dynamic, one that puzzles me to no end.

But I have written it off as one of those karmic enigmas – perhaps in another life these women betrayed my uncle in some way so that now, they’re repaying him with their allegiance.

|

| Speaking of Karma, the company has its own altar room. Perhaps the office ladies don’t use it enough. |

Every time I visit the office and see these women, some still quite young looking (though I feel this has more to do with a mental projection of their reluctance to leave a certain stage of life than with any skincare regime), I wonder, “Why don’t they leave? Why don’t they quit?” It’s a depressing sight, but I can only keep this to myself or speak in whispers, to my cousin who feels the same way.

We can fear them right now because we are young.

But who knows, one day we may know exactly how they feel when a young woman on the cusp of career or love or both, walks into the room. Or perhaps it’s just my superstitions talking. In companies all over the world (though it seems most visibly in Asia) women are trading job security for marriage. They work late hours, making it hard to socialize after work, and when the weekends come, they have barely any energy leftover to meet new people not to mention spend time with friends and family. Men go through the same thing too, but the alarmingly imbalanced ratio of women to men (the article is for Hong Kong, but Taiwan’s numbers are not too different) means that men can be far less proactive and still, some grateful young woman is likely to fall in his lap.

Regardless, I’ve vowed to never seek employment in the family business. In medical equipment and real estate, the company has made a comfortable living for all those associated. Where it has no business is Love. At least not for the office ladies.

Tainan (Part 2) – A Village

Back from Hong Kong and Shanghai, but posting my last few Tainan photos before I forget…

After visiting the temple, Dr. Chang’s friends took us to an old village, the Chiang Family Village in Lu Tao Yang. A woman in our group was actually from the Chiang Family, and the village patriarch had been her grandfather. The village is built in the old style, courtyard units connected together, and is so well preserved that the Taiwanese government declared it a National Historical Site. There was a concert there that night, held yearly at the end of New Year’s celebrations and performed by local villagers as well as professional musicians. It was a glimpse of old Taiwan, and Mrs. Chang’s father, who went with us, enjoyed himself immensely. “It reminds me of my old home in Shandong, China,” he said.

|

| The entrance to the village had tables set up filled with games for children. |

|

| Chiang children, playing games. |

|

| One of the courtyards. Some of them are for worshiping ancestors. Such as this one. Many temples are built along the same principle. |

|

| Musicians preparing for the night’s show. The stage was set in the village square. |

|

| Volunteer ladies ladled out bowls of tang yuan, or sticky rice balls in sweet broth. You eat this for prosperity. |

|

| There was a small, moon shaped pond at the head of the village. |

|

| I saw this photo in one of the courtyards. I’m guessing it is the Chiang family matriarch. |

|

||||

| Dining hall. |

|

| An eager family, waiting for the show to start. |

|

| Costumes for the show. I wondered about the one on the right. |

As we left for Kaoshiung for our own dinner, I could hear the music start. I turned around and saw the village light up.

And for tomorrow, a preview of coming attractions…

|

| Tian Tan Buddha on Lantau Island, Hong Kong. |