My mother is like a child, though not in a bad way. I marvel at her ability to marvel at the things I take for granted or give little to no thought at all – and push away thoughts of Alzheimer’s to the nether regions of my brain, hoping never to have to retrieve them – and wonder what the switches in her mind look like and who is running them. Happy, mischievous little elves, those switch operators.

“Look here!” they say, “Look there! Bet you never noticed that before.”

And obediently my mother will turn and look. Her eyes will grow wide and she will look at me with the kind of earnest surprise that only earnest surprise can generate. Her long index finger will point, and she will ask me something or other, the most obvious question. A restating of the facts themselves, but with a question mark at the end.

My reaction is always a slackening of the lower jaw and the wrinkling of the top left corner of my nose – a physical embodiment of incredulity.

“Mother,” I will inevitably say, “nothing has changed. It has always been like this.”

Last night she walked into my room and noticed that the louvers on my shuttered windows were open. Let me provide some history. Those windows have been on the south side of my room since the beginning of the house itself. The owners before us outfitted them with shutters that open towards the inside. On a sunny day, the idea was, the girl in the room could open the shutters and enjoy the flowers blooming in the side yard and smell the clean scent of freshly washed laundry sunning on the clotheslines. Such was the function of the side yard: a drying place for clean clothes, a sunning place for pretty white rose bushes or other flowers the lady of the house preferred.

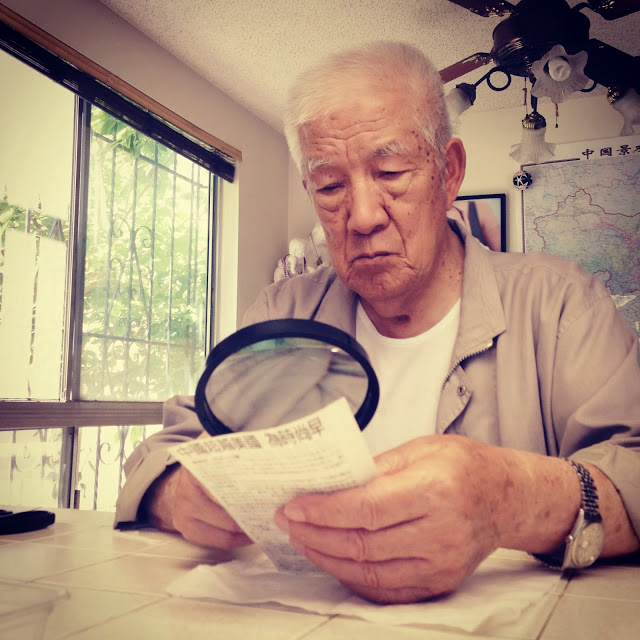

That elderly couple moved away some twenty years ago and sold their beloved one story house to a young Chinese couple with two young children. The Chinese man was quite fastidious – he was partly by nature and partly by upbringing and training punctual and organized, kept documents in files labeled by date and kept his clothes neatly hung or folded in the closet. He was not obsessive compulsive by any means, but he liked things neat and believed that everything had its place. He was raised in an orderly, tasteful house that blended spare Chinese elegance (his mother) with spots overflowing with shiny English knickknacks (his father). Despite this difference in aesthetic tastes, both parents were punctual and neat. It is odd then, that he married a woman who arrived an hour late to their first blind date and would, for the rest of their married lives, cause him to arrive at least ten minutes late and with high blood pressure to any functions they attended together. This woman was not organized by nature or by training, though to sustain the marriage she tried. She was also by nature a hoarder and this tendency extended to her love of flora.

When husband and wife moved to their new home formerly occupied by the tasteful elderly couple of Anglo-Saxon descent, the woman immediately set about filling the back and side yards with her hodgepodge of greenery. What had once been a nice, orderly aisle reserved for clean laundry and a few carefully pruned rose bushes was now overrun with pots large and small filled with odd plants of eastern origin, none of which the daughter, whose windows faced this side yard, found aesthetically pleasing. Her mother liked weird spiky plants whose arms looked like crab legs or were wide and flat like ugly green belts. She was loathe to part with any plant and her female relatives took advantage of this, and over the years, added to her mother’s unsightly collection by bringing over their own ugly houseplants that were on the verge of death.

“Here,” they said to the girl’s mother, “I no longer know what to do with this plant. Perhaps you can nurse it back to health and make it bloom again.”

|

| Potted Plants, Paul Cezanne 1890 |

It may come as a surprise to some, but a dying ugly plant does not look too much different from a thriving ugly plant. But when one is a plant hoarder, a plant is a plant. The girl’s mother also liked orchids, but these she kept hidden in a green house that sat on the hill, at the back. Instead of complain to her mother, the girl decided at a young age to keep the shutters closed but the louvers open to let in sunlight. She found the light itself pleasing, and did not think about the mess her mother had made of the side yard. At night, it did not matter. Everything was dark, and as the side windows faced the side yard, through which no one ever walked but her mother, the girl did not bother to close the louvers. Ever.

For some twenty years, it can be said, the girl’s mother would come into her bedroom at the end of the night and chat with the girl, telling her stories and doling out the advice only a mother is able to provide. The girl’s bed is positioned directly underneath the shutters, the louvers cast downward at whomever should sit or lie in the bed. They have always been positioned so, and even when the house cleaners come and wipe at the dust and alter the angle of the tilt, the girl will always, always re-position the louvers just so. See, unlike her father, the girl is more than fastidious, she is particular. Especially in regards to the position of the louvers.

They are never closed. The girl believes this takes away from the room’s dimensions. Makes it seem more narrow than it is. So there you have it, the essential point of that history: the louvers are never closed.

Back to last night. I looked up from the book I was reading and stared at her, wondering what in the world she was talking about.

“Your windows are open!” she said again, “You must close them at night!”

“Whatever for?” there was audible alarm in my voice, though my mother failed to notice and instead turned to me with alarm written over her face, as though she couldn’t believe I didn’t know what dangers lurked outside the windows of our small, quiet town.

“It’s not safe! Someone could peek inside and see you!”

“Mother, these windows face the side yard, which is not even connected to the road.”

She waved her hand at me, “You don’t understand. It’s not safe. There could be a bad man out there.”

“No mother, there are only hideous plants.”

She smiled and sat down in her usual spot on the edge of my bed, then proceeded to tell me about the peeping tom that had plagued her and her sister when they were young ladies in their teens.

“Your aunt Joannie and I shared a room and one night I felt someone looking at us, and when I looked to the window, there was a peeping tom! Leering at us right from the window! I screamed and then of course he ran off, but see, there are so many strange people out there.”

I nodded slowly, amused by both the story and my mother’s imitation of her younger self, a personality which emerges constantly and uncannily in her person’s current version. She is, despite her poor memory, someone I would deem ‘ageless.’ And yet in spite of her poor memory something about my south windows prompted a scene of her younger self. We all have those moments, I suppose.

“If I lived in a bad neighborhood in a big city, I’d keep the windows shuttered,” I assured her, “but here…” -I looked up between the louvers and scanned the darkened windows, half expecting to see a pair of bright, leery eyes, but was met with only the faint reflection of my bedside lamp – “I don’t think we need to worry about it.”

“Even so,” my mother said, “even so. You can never be too careful.” But she made no movements to close the louvers.

We chatted some more and she rose to leave, though not before taking one last look outside the windows. She saw nothing, I’m sure – it was a darker night than usual, the moon was off somewhere being bashful – but instead smiled to herself, thinking not of the peeping tom that had frightened her so many years ago but of all her darling odd plants, spiky leaves and waxy arms reaching out or hanging from the old clothesline. They stand in the dark in messy, uneven clusters like poorly conditioned soldiers of a decrepit army. Perhaps they protect me when I sleep.