|

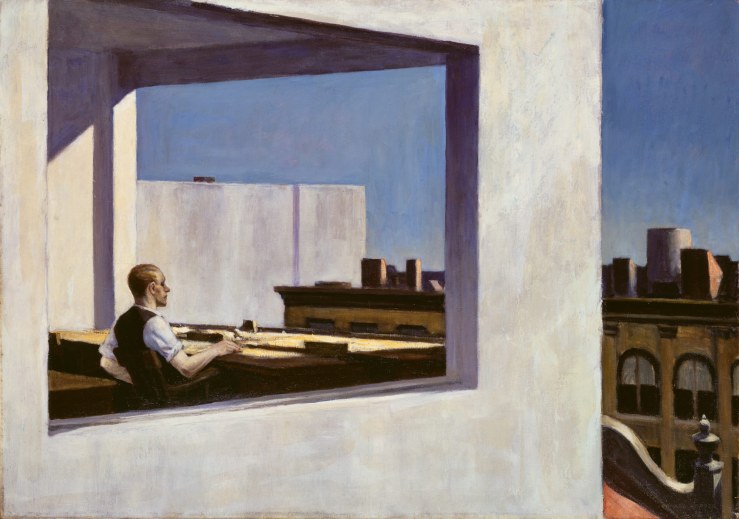

| Fifth Avenue Bridge Martin Lewis 1928. Drypoint. |

My coworkers were so different from my classmates. I thought about my workshop from last semester – a group of misfits who oddly enough, when arranged together around rectangular tables in a small classroom, seemed to fit perfectly together. There was the failed actress turned sex columnist; the former (and probably current) meth/crack/heroine addict, the spastic magazine writer with an unidentified eating disorder; the pretty but awkward Brazilian sportswriter who’d slowly gone in a downward spiral until she underwent gastric bypass and discovered that she was actually a genius and joined MENSA (“You know what we do in MENSA?” she said to me over lunch one day, “We compare medications.”)

There was the old woman who sat defensively with her shoulders hunched nearly to her ears and whose hair was so dry I feared it would burst into flames at the slightest friction. I detested her at first because her first essay sucked, and then I sort-of-kind-of reluctantly admired because she took the writing teacher’s advice and made it much better when it was workshopped again. There was the Indian girl who had, back in India, been in an abusive relationship. She had fought with her parents until they agreed to let her come study in the States and was now, according to Facebook at least, in a loving same-sex relationship. And there was the professor, in her late thirties and beautiful in a devil-may-care way and slightly aloof. A winning combination for any professor or woman, for that matter. Everything about her I learned from the sex-columnist and other classmates who adored her and wanted very much to take another workshop with her, though I felt distanced from her, partly because she didn’t seem, most of the time, to want to be in the classroom. She was an adjunct and had another real, full-time job as the editor of an online magazine. I went to visit her once at her office and we had a short conversation (“I’d like you to speak up more in class,” she said. I nodded. “Anything else?” I shook my head. “Okay then.”) before it became clear that she had to get back to work, real work. The kind that paid the bills.

And there were my counterparts – the girls like and unlike me – who had grown up in loving suburban families, who had never done drugs (until they did finally do drugs), who had held a string of odd part-time jobs (strip club waitress, 9/11 archivist, Costco cashier assistant), who had traveled and who wanted to continue traveling but who, at the same time, wanted some sort of internal anchor to keep us centered even when we were in the air. We could write well about a few things, but weren’t sure in the long run if that’s what we could do without running out of words or energy.

Suddenly, with birthday pizza on my lap in the copy room of Company X, I felt like I was in class again – Introduction to Real Life…?– surrounded by the corpses of English majors past that had now been repurposed into living breathing copywriters, all dressed almost exclusively in Madewell and J. Crew (the higher up you are the more full-priced items you can buy!). I got a weird sinking feeling that I and my thrift-store wearing, Brooklyn-living (except I live in the Upper West Side), part-time job-holding, chain-smoking classmates were fooling ourselves in thinking that writing for ourselves could somehow bring us the emotional and material life we wanted. It seemed that these girls, even that damned playwright who seemed to fit in so well despite his side job (though seriously, which job did he consider his “side” job?) must have, at some point, had similar dreams. Until the morning they woke up and turned uncomfortably onto their sides, seeing through the open window, “Oh! Reality.”

I wasn’t depressed, not quite, not yet, but I left the office feeling like a new cog in a giant, though much more fashionable, start-up-ish wheel. It didn’t help either that the walk home that night was bone-chillingly cold. The sounds of the street, usually welcoming after spending an entire day cooped up in my studio, seemed abrasive. I was now one of the hundred thousand people walking home from a tiring day at work. The wind hit my cheeks in sharp, icy slaps. I wasn’t underdressed, but was cold to begin with because I had sat and sat, staring at painfully cheery copy until my innards froze from physical inactivity and my right hand, on the mouse, had turned blue as it usually does when I leave it in that position. The light above my work desk had gone out so my corner had been a monotonous grey except for the blinding glow of the computer screen.

I frowned about these things as I went down into the subway. I frowned as I stood waiting with other people just getting off work, most of them also frowning or bearing no expression at all. In the subway, a man played Spanish guitar and several people frowned a little less as they walked by, deciding after a few steps to return and drop a dollar or two in his open guitar case. On the train, I frowned as I was shoved to the left side doors, then to the right side doors, then towards the middle of the car. I frowned too, when a dirty old homeless black man boarded and began to sing, “I’ve got sunshine on a cloudy day,” informing us that he was in fact, “singing for supper.” I looked away, still frowning. When he left for the next car, I looked at the young men and women and at the not-so-young men and women around me, most of them tired, all of them trying to make a living in various fields. I guessed that most too, had more responsibilities than I, to children, to wives, husbands and parents. To themselves.

I wasn’t being fair. I didn’t have to be, but I ought to try. Especially with former English majors who had read the same books I read, loved the same authors and poets and used, when they could, the same language. Their jobs didn’t define them anymore than an MFA would define me, than the sour smell of the homeless man defined him. They had merely gone a different way and I was passing through, looking.

I stopped frowning, but I didn’t smile either. I was dreading the stairs up to my apartment. I held my keys ready as I came out from underground and walked passed the two bums, one of whom was already fast asleep, himself undoubtedly having gone through a trying day and the other still “working,” though he shivering, stomped his feet and blew onto his hands. His gloves were thin and filled with holes. His sign was crumpled, but I could make out the two words that seem to appear in every homeless man’s message: “Help…God.”

“I get it, God,” I thought, looking up, “I get it.”

In the dark chilly skies above my warm apartment, God shrugged. He hadn’t said anything.